I read this on twitter.

And I question it.

Why question it?

Because it seems to suggest that the masks of commedia depicted Jewish and people and other racial types. And that these days we should be better.

But I think this is wrong. From my study of commedia, it has never been suggested that the stock characters noses (or the colour of the leather) was meant to represent race. I think this is something we see not something that was.

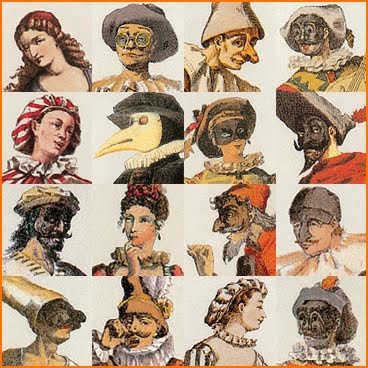

In reference to colour - it’s just not true. The same mask is reproduced in many colours - tan, red, black. Pantalone’s mask, for example, could be black. But - and here it’s possible to be categorical - this was not supposed to represent African descent.

We now see it. Now, why would you want to bother your audience with worrying about this? For reasons of courtesy and for reasons of signifiers changing and for reasons of not getting in the way of the purpose of the mask (whether that’s teaching or theatre-making). Of course, it makes absolute sense to strip out the darker masks. It’s an easy fix. Why would you not?

But it’s important to note we aren’t improving on ancient racism that actually existed. We are seeing it in a place where it was not. This is not to say that it did not exist (the Turkish or Moorish masks would surely have been dark) - but Pantalone’s black mask did not mean he was to be read as black. It is our own eyes that see the colour as representative of race. We are not fixing an ancient wrong.

The noses are more complex.

However, I am not convinced that she is right.

(Here I should say, I am no commedia expert. I studied it practically in Italy for a month in 2002 with Antonio Fava, and I have read various books. But I do not teach it (here I would look to Philippe Gaulier, Lecoque, Peta Lily etc). Nor have I ever had the urge to use it within my own practice - it’s not, at the end of the day, my style.)

Still. The first issue is that I had never understood any of the characters I worked with to represent Jewish people. Commedia is a polylinguistic theatrical form, using characters with different backgrounds, and the scenarios and characters are endlessly adaptable. But the core characters are in essence archetypes of Christian Italian society :

Zanni - the Servants (traditionally speaking various Italian dialects)

Magnifico - the Master : the most famous being Pantalone (Venetian)

Dottore - the Professor (Bolognese)

Innammorate - the Lovers (Tuscan or various)

Capitano - the Captain (often Spanish)

It is very difficult to imagine that these characters could be Jewish, simply because Italian society was comfortable with its anti-semiticism.

Pantalone - the Magnifico - is the highest in social status of all characters. He’s the ‘master’ archetype in One Man Two Guvnors. I find it extremely difficult to imagine that he could possibly have been considered Jewish.

Commedia is becoming popular mid-16th Century. In the counter-reformation, the Catholic church reinforced a highly anxious and extreme anti-semitism. Hence, Jewish refugees were fleeing to Italy after being expelled from Spain. The Papal states of central Italy outlawed usury and Rome built her first ghetto - all of this pushed Jewish refugees further north, where it was at least possible for Jews to live and work, even within strict limitations. The Northern states were more involved in the Mediterranean trade routes, which benefitted from Jewish expertise in the Levant, and banking practice, so the Princes of the north tried to circumnavigate Papal ruling (to different degrees). Venice already had a ghetto (ghetto is Venetian dialect); Florence built hers in the 1570s; but the most welcoming state was Mantua.

Mantua is a curiousity in Theatre historic terms because part of the deal struck with the Jewish community was that they would provide theatre shows. Hence the Mantuan Jewish population rose from 200 to 1800 over the 16th century. There are a number of Jewish theatre stars of the 16th Century on the Mantuan scene. Most notably producer/writer/director Leone de’ Sommi who wrote the first ever handbook on theatre direction in Europe. And Madama Europa, the first Jewish Soprano opera star and in fact one of the first opera stars full stop. But this is another story, not directly relevant to the point in question, since the style of the Jewish theatre was not strictly speaking Commedia.

Anyway… The overview is that in the 16th century, anti-semitism was once again growing.

I understand the long nose (naso lungo) of the masks to be Roman in origin. See the pictures below of Roman theatre 200BC - before the Roman conquest of Judaea and well before Christianity. The noses are very similar and so the origin is pre-christian-anti-semitism. Further, there are multiple characters with long nosed masks and they are categorically not all Jewish characters.

None of this is to say that there aren’t ever Jewish characters in commedia. Erith Jaffe-Berg writes about the outsider characters (the ‘turks’, the gypsies, the armenians, the jews) in her great book, Commedia dell’Arte and the Mediterranean. And it is clear that these Jewish characters would be presented anti-semitically, by default. As you see in the English Theatre.

The “Maschare da ebrei.” (see in Francesco Bertelli) is a rare woodcut showing a definitively Jewish character. Jaffe-Berg says it is the only single print of a Jewish commedia character that she has seen. I won’t put it here but you can find it if you want. And in the props list there would be listed Jewish masks and badges alongside the Turk etc.

But this only emphasises to me that the other characters are not Jewish. Antonio, The Merchant of Venice, cannot be Jewish. Because Shylock must be.

OK. So does it fucking matter? Because this shows that Commedia is antisemitic?

Well. I have never seen or even heard of a Jewish mask in my studies. And Jaffe-Berg points out ‘this won’t be a mask most students of commedia are familiar with’. The only outsider I’ve even seen used on a relatively regular basis is the Strega (witch). And, of course, Commedia introduced female actors onto the European stage, many of them running their companies - so Commedia is intrinsically more equal than the English stage in gender politic.

Jews were represented in Commedia. And when they were represented, it was probably, usually, laced with anti-semitism. I would not begin to try to deny this self-evident truth.

Given that, there are some complicating factors.

In England, the Jews were exiled for 350 years until Cromwell opened the doors. So Merchant of Venice would have been performed to a Gentile London. Shylock would be a purely exotic character.

But - in Italy? In Livorno, with its trade routes open to the Levant, relying on the expertise of Jewish middle-men? Or Mantua? Where Commedia shows from visiting companies such as the Gelosi were programmed alongside the productions of the famed Jewish playwright, Leone de Sommi and his company of Jewish artists? Where the court would be entertained by Madama Europa and her brother, the eminent composer, Salamone Rossi, potential collaborator with Monteverdi?

It is possible that the presence of the Jewish population could heighten the antisemitism of the Christian/secular productions. Of course. But Jaffe-Berg suggests that there may have been an element of theatrical collaborations between the different artistic companies - the Gentiles and the Jews. Thus, it is even possible that Jewish artists may have performed in Commedia dell’arte. (They certainly performed masked comedy - De Sommi is referenced as producing such a show for the court).

A last note on this - it is tempting to see the ‘Christians’ as a homogenous group. But the commedia troupes were made up of people who did not necessarily speak the same language as each other (Venetians, Neapolitans, Tuscan etc). And they were foreigners where-ever they went. Italy was not a country. And touring was not in any way a comfortable profession for nice people.

Artists sometimes bought protection in cities when they travelled. One of the most famous of the Gelosi had been captured and enslaved for 7 years (and slavery was becoming more common with the growth of trade). They were often treated with little respect. In England the Puritan rule would class travelling players vagabonds - technically punishable by death. To be an actor was not in any way the rather upper middle class profession we assume it to be today.

I say this not to suggest that this means it could not be anti-semitic, but to highlight that these companies of artists were themselves seen as gypsies and outsiders. Some may reach the stars - but even so, a commedia troupe was whipped out of the court of Louis XIII for political subversion.

Who knows who was really on those stages? And behind those masks?

MODERN COMMEDIA

In 20th/21st century theatre, the most famous artist of the Commedia dell’Arte has got to be Dario Fo (1926-2014). He is not purely a commedia artist. But he’s an expert, and it’s obvious to see where the influence lies.

For Fo, the political subversive roots of commedia were absolutely crucial. Fo himself was a fiercely political anti-fascist. His family was active within the anti-fascist resistance in WW2, though Fo himself was drafted into Mussolini’s army aged 16. And there is no doubt that the theatre of Dario Fo and his wife and collaborator, France Rame, was explicitly subversive and anti-fascist.

After the war, Fo’s left-wing theatre productions received bomb threats from the far right and he himself was arrested and threatened. But the violence was most brutally shown to Franca Rame, who collaborated on so many of his productions. She was kidnapped, tortured and raped by neo-nazis in 1976.

This does not mean that Commedia could not be both left-wing subversive and anti-semitic of course. Anti-semitism can be the achilles heel of a certain anti-capitalism, if the mistake is made of aligning Jewish history of banking specifically with Capitalism.

That is what the Royal Court did by naming their Elon Musk Christian banker, Hershel Fink. Because that sounds like a capitalist’s name. My main discomfort is the question of whether, with the best will in the world, that is what is happening when people look at Pantalone (probably deriving from Piantalone - the merchants of Venice), with his gold and his girls and his money. And assume he must be Jewish.

As I bring up this horrific incident with Rame, I feel uncomfortable - am i using it to make a point? Perhaps. But I think why it makes me feel so strongly is that Fo and Rame were experts in commedia. They studied it. They knew it. And they shared it. And they put their bodies in it.

It’s not good enough to just dismiss all that work as antisemitic and then, when asked to elaborate, simply say I’M NOT AN EXPERT IN COMMEDIA and then talk about anti-semitism in the middle ages, which is basically the wrong fucking century.

If you’ve got nothing to say, then not speaking is an option.

But if you dismiss the work that was the lifetime commitment of artists like Fo and Rama and then refuse to elucidate exactly what part of the ‘fucking commedia’ is the problem, while sounding like you know what you’re talking about?

I really want to know what precisely was meant by that - that is all I was asking.

It’s not good enough.